On 15 November, 2025, the International Khatme Nubuwwat Grand Council convened a large gathering at Suhrawardy Uddyan in Dhaka and announced a year-long, nationwide campaign demanding that the Bangladeshi government formally declare the Ahmadiyya Muslim community (also often colloquially and pejoratively referred to as “Qadiani”) non-Muslim, bar them from mosques, confiscate their religious literature, and impose a social, political, and economic boycott. Around 90 clerics and political figures from Bangladesh and abroad participated, with noted representatives from major Islamist as well as other political parties seemingly publicly aligning themselves with these demands. Amongst others, representatives from the Bangladesh Nationalist Party, Bangladesh Jamaat-e-Islami, Islami Andolon Bangladesh, Bangladesh Khelafat Majlis, and Hefazat-e-Islam Bangladesh were in attendance.

In the days following the rally, we observed a notable volume of user-generated content (UGC) on Facebook, the most popular social media platform in the country, echoing and amplifying the event’s core messages. This report analyses a targeted sample designed to surface early narrative, coded into six thematic categories and assessed against Meta’s Hateful Conduct Policy as well as Bangladesh’s constitutional and statutory framework.

Across themes, content reviewed calls for state-sanctioned exclusion of Ahmadiyyas from religious and civic life, classifies them as infidels, threatens their continued residence in Bangladesh, and ties these demands to explicit political promises. Such calls appear to conflict with core constitutional guarantees of equality, non-discrimination, religious freedom, the prohibition of abusing religion for political purposes, and other freedoms enshrined in Articles 12, 27, 28, 31, 32, 33, 35, 36, 38, 39, and 41 of Bangladesh’s Constitution. Moreover, they may constitute offences under the Penal Code, 1860—such as promoting enmity between classes along racial and religious lines, hurting religious sentiments, criminal intimidation, and criminal conspiracy—as well as under section 26 of the Cyber Security Ordinance, 2025, which criminalizes publishing and promoting religious or ethnic violence and hate speech in cyberspace. The messages of the content also appear orthogonal to Meta’s Hateful Conduct Policy, as well as its commitments under the Corporate Human Rights Policy.

Given Bangladesh’s documented history of anti-Ahmadiyya discrimination and violence, including lethal attacks and large-scale arson in Panchagarh in 2019 and 2023, this surge of offline and online hate cannot be treated as abstract rhetoric by fringe groups. It is a coordinated campaign by established religious and political groups that not only contravenes platform policies but also appears to sit squarely at odds with Bangladesh’s own constitutional commitments and criminal law framework. The content documented here should therefore be understood as both an early warning indicator of potential offline violence and a possible breach of domestic law requiring urgent attention from state institutions, platforms, and political actors alike.

Objective and Scope

This report pursues three primary objectives. First, it documents the surge in anti-Ahmadiyya content on Facebook in the immediate aftermath of the Suhrawardy Uddyan rally held in Dhaka on 15 November, 2025. Second, it analyzes the dominant narratives and demands contained in the content reviewed, with particular attention to calls for state-sanctioned exclusion, dehumanization, expulsion, and economic targeting of the Ahmadiyya Muslim community. Third, it examines the extent to which these narratives align with, or stand in tension with, Meta’s Hateful Conduct Policy and Bangladesh’s constitutional and statutory framework.

The scope of the analysis is intentionally narrow; it is confined to a small corpus of publicly accessible Bangla-language Facebook posts identified through targeted keyword searches (including ‘আহমদীয়া’, ‘কাদিয়ানী’, ‘কাফির’, ‘খতমে নবুওয়ত বাংলাদেশ’ and ‘অমুসলিম’). It does not extend to other platforms (such as YouTube, TikTok, Telegram, or closed WhatsApp groups), nor does it attempt to map the broader offline ecosystem of sermons, printed materials, and organizational activities. The report should therefore be read as an early, qualitative diagnostic of an online hate surge, rather than a comprehensive account of all anti-Ahmadiyya mobilization efforts in Bangladesh. A more detailed explanation of the report’s methodological choices is elaborated in the Methodology and Limitations sections.

In addition, the report deliberately refrains from providing direct links to the posts in question in order to avoid further amplifying their content. The underlying dataset can be shared with researchers or relevant authorities upon request.

Background

Discrimination and violence against the Ahmadiyya Muslim community in Bangladesh are neither new nor isolated. Founded in 1889 by Mirza Ghulam Ahmad in Qadian, India, the Ahmadiyya movement emerged as a revivalist movement within Islam. Ahmadiyya consider themselves Muslim and interpret the “finality” of prophethood in a spiritual sense; many mainstream Muslim groups, however, regard this belief as heretical. Across South Asia, this theological dispute has been politicized, turning Ahmadiyya into a convenient “other” for religious parties and transnational clerical networks.

In Bangladesh, Ahmadiyya have lived and practiced since the early 20th century, but their status has repeatedly been challenged by conservative religious movements demanding that the state formally declare them non-Muslim. These campaigns often emerge at the intersection of religious orthodoxy, party politics, and street mobilization. Over the past two decades, Ahmadiyya mosques and properties have been attacked, their literature has faced attempts at restriction, and local communities have been subjected to boycott calls and intimidation. These dynamics have also extended into the economic sphere, with recurring allegations and boycott-oriented messaging directed at commercial entities such as the PRAN-RFL Group in multiple episodes, including 2021 and the period following the 15 November rally.

Events in Panchagarh, a district in northern Bangladesh, illustrate how quickly this hostility can escalate. In March 2023, for example, violence against the Ahmadiyya Muslim community in the district left two people dead, injured many others, and resulted in around fifty homes being burned or vandalized. A few years earlier, in February 2019, 15-20 Ahmadiyya houses and shops in the same district were attacked and set on fire, injuring at least 30 people. In 2015, a suicide attack targeting weekly prayers left one person dead and wounded at least a dozen others. These attacks are part of a longer history in which the Ahmadiyya Muslim community has repeatedly been subjected to targeted violence across Bangladesh.

The regional context makes this vulnerability even sharper. In Pakistan, Ahmadiyya are constitutionally declared non-Muslim and face criminal penalties for “posing” as Muslims; in Saudi Arabia, they cannot enter as Ahmadiyya to perform religious rites. Bangladesh, while constitutionally committed to equality and religious freedom, sits within this broader ecosystem of anti-Ahmadiyya rhetoric and systemic exclusion. When rallies in Dhaka feature speakers from Pakistan, India, Nepal, Egypt, and Saudi Arabia, they import not only theological arguments but also political templates from jurisdictions where Ahmadiyya have already been systematically disenfranchised.

Notably, this pattern of targeting should be understood within a broader context of vulnerability for minority groups in Bangladesh. Episodes of violence against Hindus, Buddhists, and Christians, attacks on Shia imambargahs and Sufi shrines, discrimination against Rohingya refugees, and the longstanding marginalization of Indigenous peoples in the Chittagong Hill Tracts demonstrate that religious and ethnic minorities have often borne the brunt of politicized identity conflicts. These incidents reveal a wider ecosystem in which majoritarian narratives, local power struggles, and impunity for communal violence intersect, enabling mobilization against vulnerable groups with limited risk of accountability. Situating the anti-Ahmadiyya campaign within this landscape is therefore essential: it reflects not an aberration but a recurring dynamic in which minority identities become sites of contestation, instrumentalization, and, at times, organized violence. However, what makes the anti-Ahmadiyya mobilization particularly concerning is the extent to which it has migrated from the margins into the mainstream of party politics over the last few decades, drawing explicit demands for state action—legal designation, restrictions, and exclusion—from actors who are plausibly positioned to shape future policy.

Within Bangladesh’s own constitutional framework, however, the state is constitutionally bound to uphold principles of secularism; non-discrimination; equality before law; freedom of movement and assembly; freedom of expression and religion. Using religion for political gain and fueling communal hatred runs directly against these constitutional commitments. The legal analysis in this report shows that online calls to declare Ahmadiyyas non-Muslim, expel them, restrict their movement, or subject them to economic boycotts are not just morally troubling—they appear to be in direct tension with the Constitution of Bangladesh and may constitute offences under the Penal Code, 1860 and the Cyber Security Ordinance, 2025.

It is in this historical, regional, and legal context that the 15 November, 2025 rally at Suhrawardy Uddyan must be understood. The event did not merely stage a theological contention; it launched what appears to be a well-organized, politically backed, sustained campaign demanding that the state declare Ahmadiyya non-Muslim, ban their access to mosques, and confiscate their religious literature—effectively advocating for civic, political and social isolation of the community. The participation of well-known representatives from major political parties and religious groups indicates that anti-Ahmadiyya demands are being actively drawn into the mainstream of party politics rather than confined to fringe groups, a development made more consequential by the likelihood that these parties and groups are plausible future governing actors and policy-setters. Additionally, the choice of venue further amplifies the rally’s political signalling. Suhrawardy Uddyan is not an ordinary public space: it is closely associated with pivotal moments in Bangladesh’s national history, including landmark speeches during the independence movement. Holding a mobilization demanding state-backed exclusion from this ground lends the campaign an added layer of symbolic legitimacy and national resonance.

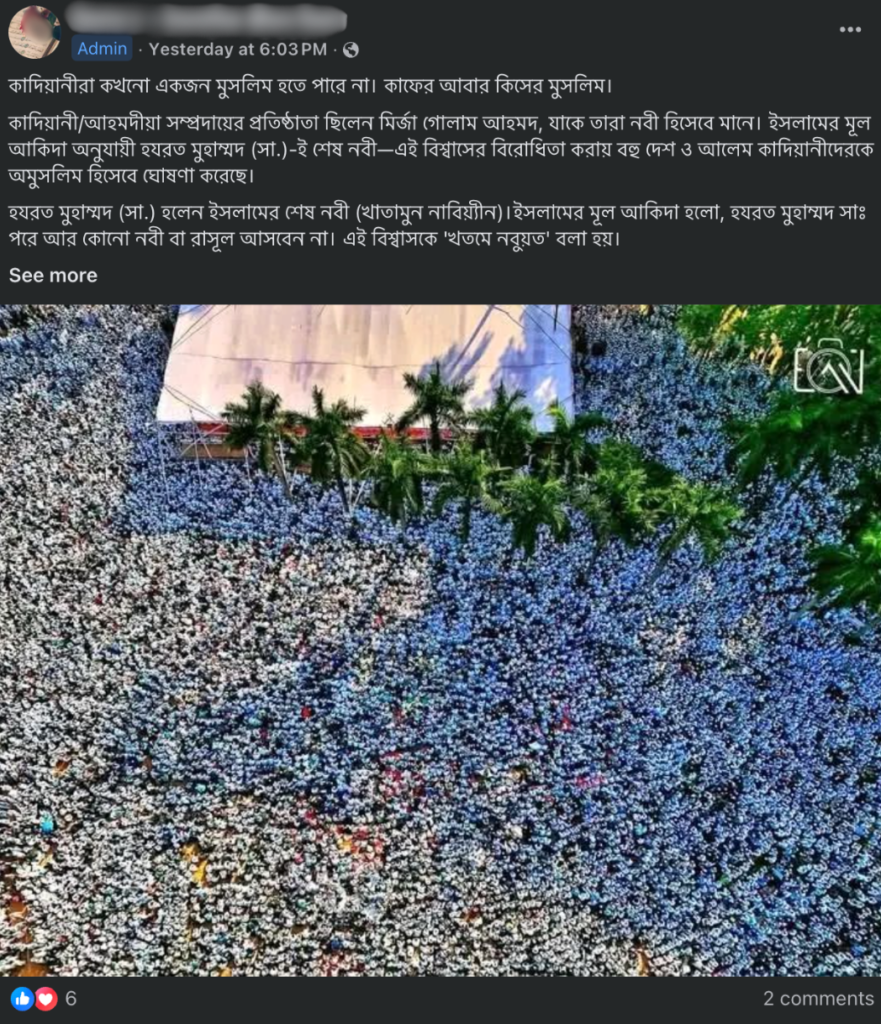

Social media is the connective tissue between such offline campaigns and everyday public discourse. Following the rally, Facebook was inundated with content labeling Ahmadiyya as kafir (infidels), calling for their expulsion from Bangladesh, demanding a formal state declaration of their non-Muslim status, and promoting economic boycotts against companies alleged to be Ahmadiyya-owned. In some posts, users endorsed the messages of political actors who explicitly pledged to implement these demands if they came to power. This digital layer matters because it contributes to the normalization of radical ideologies and sectarian divide, while enabling the rapid dissemination of messaging at scale and coordination of harassment; this, in turn, creates a permissive environment for offline violence, particularly in a context where violence against Ahmadiyya has already taken place and where the law, at least on paper, prohibits exactly this kind of incitement and discrimination.

By systematically documenting and analyzing this hate surge, and by locating it within both Bangladesh’s history of anti-Ahmadiyya violence and its constitutional and statutory framework, this report seeks to show that the current campaign is not only dangerous but also legally indefensible.

Analysis

4.1 Thematic Findings

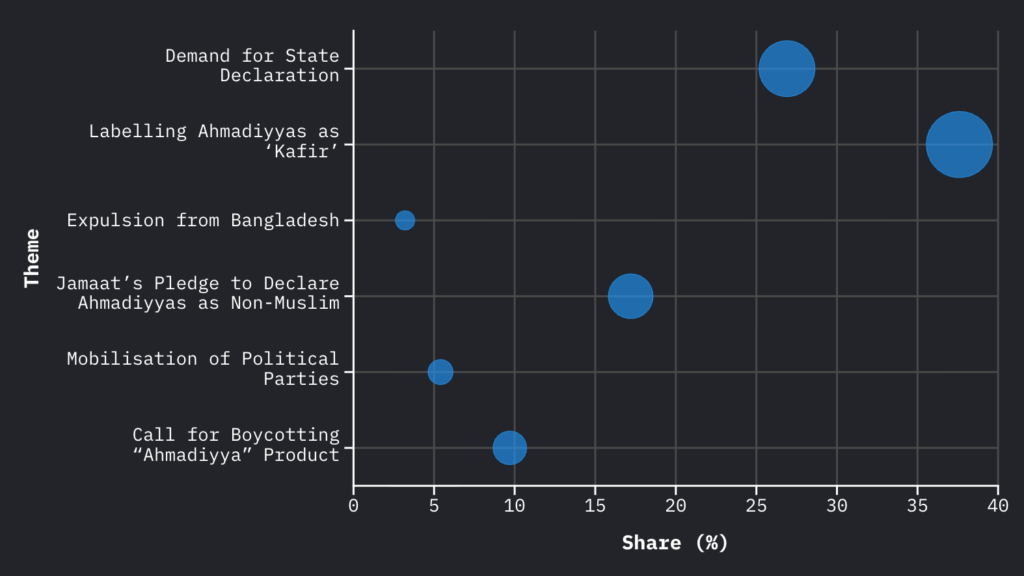

- Demand for State Declaration: Of the total UGC collected for this analysis, approximately 27% demanded that the Bangladesh government officially declare Ahmadiyyas to be non-Muslims. These posts closely echoed the core demand of the Khatme Nubuwwat movement, which organized the 15 November 2025 rally at Suhrawardy Uddyan in Dhaka.

Beyond the formal declaration, several posts further argued that Ahmadiyyas should not be allowed to identify themselves as Muslims or to receive the benefits and recognition that, in the posters’ view, flow from that identity as citizens of Bangladesh.

Taken together, this theme advances the view that a religious minority’s legal status, civic belonging, and access to rights should be contingent on a majoritarian theological verdict—and that the state should be used to enforce that verdict.

- Labeling Ahmadiyyas as “Kafir”: Around 37.6% of the UGC explicitly labeled Ahmadiyyas as kafir (infidels). Many of these posts went further, declaring that any individual, political party, or organization that refuses to use this label for Ahmadiyyas should also be treated as kafir.

This was the most common theme in the dataset. It does not simply express theological disagreement; rather, it seeks to affix a pejorative and stigmatizing religious status on Ahmadiyyas and to police the boundaries of acceptable opinion by threatening anyone who dissents with the same label. In doing so, it entrenches a hierarchy of “true” and “false” Muslims and creates a climate in which hostility and discrimination against Ahmadiyyas and their perceived allies can be justified as a religious obligation; this is further witnessed in the calls for boycott of products allegedly associated or owned by members of the Ahmadiyya Muslim community.

- Expulsion from Bangladesh: Around 5.4% of the UGC argued that Ahmadiyyas should “have no existence” in Bangladesh, asserting that the country is “only for Muslims.” In these posts, the demand goes beyond theological exclusion and calls into question the Ahmadiyyas’ very right to exist and/or live in the country as citizens.

By framing Bangladesh as an exclusively Muslim country and openly denying Ahmadiyyas any place within it, this theme crosses from discrimination into expulsion rhetoric. It suggests that citizenship, safety, and belonging are conditional on conforming to a particular religious identity, and it implicitly legitimizes the idea that forcing Ahmadiyyas out—socially, economically, or physically—is both acceptable and desirable.

- Jamaat’s Pledge to Declare Ahmadiyyas as Non-Muslim: Approximately 3.2% of UGC referenced a political pledge by Bangladesh Jamaat-e-Islami, asserting that Ahmadiyyas would be declared non-Muslim by the government if the party came to power. These posts echoed a statement made by its Assistant Secretary General Rafiqul Islam Khan at the Khatme Nubuwwat rally on 15 November 2025, where he publicly declared that, under a Jamaat-led government, Ahmadiyyas would be officially recognized as non-Muslims.

Although it remains unclear whether this reflects the official party stance, this theme is significant because it appears to translate anti-Ahmadiyya sentiment into an electoral promise. In doing so, it shifts the campaign from purely rhetorical and clerical pressure into the realm of formal politics, signaling an intention to use state power to enforce theological exclusion.

- Mobilization of Political Parties: About 17.2% of the UGC consisted of posters, leaflets, banners, and promotional videos related to the Khatme Nubuwwat rally on 15 November 2025 in Dhaka were circulated on social media in the days leading up to the event. On closer inspection, these mobilization materials were found to be produced and shared by political parties and their associates, rather than only by religious groups.

Some of these posts not only advertised the rally but also carried a clear message that the Khatme Nubuwwat movement would “not stop” until Ahmadiyyas are officially declared non-Muslims. This theme highlights that the campaign is not a spontaneous or purely clerical effort: it is being actively amplified and normalized through the organizational machinery of political parties, helping to transform sectarian demands into a broader mass mobilization. Moreover, while the campaign is framed as year-long, the messaging surrounding the rally and its subsequent amplification on social media indicate that the demands are being positioned as part of a longer-term political agenda, to be pursued until the stated objectives are achieved.

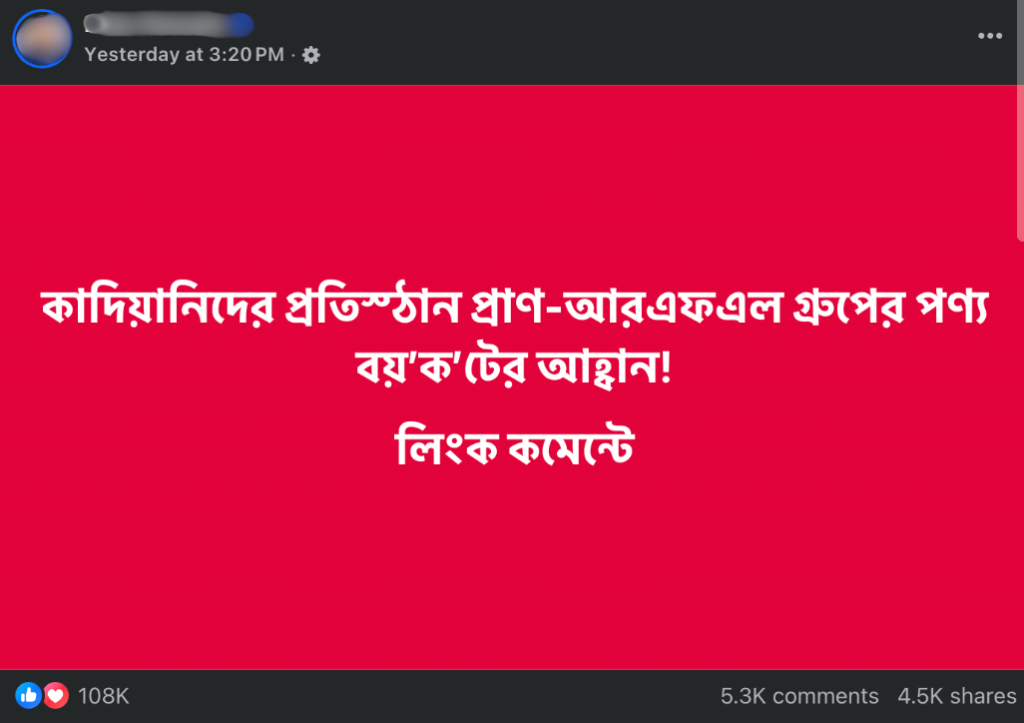

- Call for boycotting “Ahmadiyya” products: A recurring theme, reflected in roughly 9.7% of the analyzed UGC, were the calls to boycott products from companies allegedly owned by members of the Ahmadiyya Muslim community. Several posts specifically targeted the PRAN-RFL Group, circulating claims that it is “Ahmadiyya-owned.” These supposed ties were repeatedly used as the basis for urging consumers to avoid products from PRAN-RFL Group.

By framing ordinary commercial goods as “Ahmadiyya products,” this theme seeks to extend religious stigmatization to the economic sphere. It encourages collective punishment of businesses based on alleged religious identity and risks both material harm to the targeted company and further social isolation of Ahmadiyyas, regardless of whether the underlying claims are true.

4.2. Policy and Legal Assessment

- Meta’s Hateful Conduct Policy

We assessed the six thematic categories identified in the dataset against Meta’s Hateful Conduct Policy in order to determine the extent to which they constitute hate speech or incitement directed at the Ahmadiyya Muslim community. The analysis focused on whether the content advocates discrimination or exclusion on the basis of religion, deploys dehumanizing language, or signals or legitimizes future harm. Based on our analysis, the content reviewed across all six themes appear to violate Meta’s Hateful Conduct Policy, as outlined below.

- The theme “Demand for State Declaration” advances calls for the formal designation of Ahmadiyyas as non-Muslim by the state. In doing so, it advocates systemic exclusion on the basis of religious belief and seeks the denial of rights and recognition that attach to Muslim identity in Bangladesh.

- The theme “Labeling Ahmadiyyas as ‘Kafir’ involves the repeated description of Ahmadiyyas as kafir or “infidels”, sometimes extending this label to anyone who refuses to endorse it. This discourse functions as dehumanizing and stigmatizing speech, constructing Ahmadiyyas as religiously inferior and outside the moral community of “true” Muslims.

- The theme “Expulsion from Bangladesh” explicitly asserts that Ahmadiyyas should have “no existence” in Bangladesh and that the country is exclusively for Muslims. This constitutes an open advocacy of expulsion, grounded in exclusionary nationalist rhetoric, and directly targets the continued residence, movement, and citizenship of the Ahmadiyya Muslim community in Bangladesh.

- The theme “Jamaat’s Pledge to Declare Ahmadiyyas as Non-Muslim” links anti-Ahmadiyya sentiment to political commitments, with party representatives pledging to use state power to declare Ahmadiyyas non-Muslim if elected. This theme represents a form of politically mediated hate, signaling future harm and employing exclusionary rhetoric as a tool of political intimidation and mobilization.

- Mobilization of Political Parties documents the active role of party structures and affiliated actors in disseminating rally materials and reiterating that the campaign will “not stop” until Ahmadiyyas are declared non-Muslim. This reflects a sustained, organized campaign of exclusion by and through political actors, rather than isolated or spontaneous expressions of individual prejudice. This further underscores that, although the campaign is framed as year-long, these demands are a part of a longer-term political agenda to be pursued until the stated objectives are achieved.

It is pertinent to note that Meta has previously deployed so-called “break glass” measures in crisis situations to curb the spread of harmful content. These measures consist of temporary, exceptional adjustments to the platform’s ranking algorithms and enforcement protocols, designed to slow the dissemination of potentially dangerous or highly viral posts and to increase the intensity of content oversight. Many of these interventions, first activated around the 2020 United States presidential election, were rolled back shortly thereafter and only reintroduced following the events of 6 January 2021 at the U.S. Capitol, when it became apparent that the risk of violence remained elevated.

In parallel, Meta has consistently promoted its AI-driven content moderation as the primary mechanism for addressing harmful material at scale, emphasizing the role of advanced machine-learning systems in identifying and removing violating content without reliance on user reports. For example, Facebook’s integrity team reported that by 2020, its systems were proactively detecting and removing approximately 97% of the hate speech ultimately taken down from the platform, prior to any user flagging. With subsequent advances in artificial intelligence, particularly the advent of large language models, Meta’s overall strategy appears to have shifted away from labor-intensive human review and towards an increasing dependence on automated moderation.

Against this backdrop, the findings in this report suggest an enforcement failure on Meta’s part. Multiple items in our sample appear potentially inconsistent with Meta’s Hateful Conduct Policy, yet remained visible during the sampling window and continued to circulate.

Additionally, in 2021, Meta published its Corporate Human Rights Policy, which affirms that people are “equally entitled” to human rights “without discrimination” and commits the company to respecting internationally recognized human rights under the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights as well as the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination. In this light, the continued circulation of content calling for exclusion, discrimination, or threats against a religious minority appears orthogonal vis-à-vis Meta’s stated human rights commitments, even where the company’s internal enforcement actions are not externally observable.

Meta’s own governance and precedent-setting review process highlights that the company is expected to take heightened risk and the protection of vulnerable groups seriously in contexts where online speech can plausibly translate into offline harm. In one 2024 decision relating to Pakistan’s national election, the Oversight Board upheld a content moderation decision by Meta to remove a post containing an accusation of blasphemy against a political candidate, given the potential for imminent harm in a sensitive, fast-moving electoral environment. The decision by Meta primarily anchored on the “outing risk group” status of the public figure. Moreover, in July 2025, the Oversight Board found that a Facebook comment stating that Romani people “should not exist” to be a direct attack on an ethnic group, and therefore a violation of Meta’s Hateful Conduct Policy. Although the policy does not contain the framing anymore, internally, the company does follow the prohibition of content that calls for exclusion or segregation of communities or people. Other decisions reflect similar concerns regarding Meta’s failure to enforce its own policies and commitments, including specifically in relation to racial and religious inflammatory content; it highlighted that the Oversight Board has “repeatedly raised concerns about underenforcement of content targeting groups that have historically been and continue to be discriminated against.”

- Bangladesh Constitutional and Statutory Framework

We examined the relevant provisions of Bangladeshi constitutional and statutory law to assess the legality of the forms of expression documented across the six thematic categories in the dataset. The review focused on whether the content directed at the Ahmadiyya Muslim community contravenes constitutional guarantees of equality, religious freedom, and non-discrimination, as well as whether it falls within established criminal prohibitions relating to incitement, threats, hate speech, and the promotion of communal disharmony. Based on our analysis, the content reviewed across all six themes appear to violate multiple constitutional and statutory provisions.

Bangladesh’s Constitution provides explicit protections against the misuse of religion for political mobilization and prohibits discrimination on religious grounds. Content calling for the state to declare Ahmadiyyas non-Muslim or kafir, urging their expulsion from the country, or advocating state-sanctioned discrimination, including in the form of pledges by political actors to implement such measures if elected, appears inconsistent with multiple constitutional principles. These include the guarantees of equality before the law and equal protection of law (Articles 27 and 31); the prohibition of discrimination on the basis of religion (Articles 12 and 28); the protection of life, liberty, and freedom from arbitrary state action (Articles 32, 33, and 35); the right to free movement and residence within Bangladesh (Article 36); the right to freely express themselves and to profess, practice, and propagate one’s religion (Articles 39 and 41). Taken together, these provisions indicate that the types of exclusionary and discriminatory demands identified in the dataset contravene core constitutional safeguards.

On the contrary, the Constitution recognizes secularism as a guiding principle and explicitly mandates the elimination of communalism in all its forms, and explicitly prohibits the granting of political status in favor of any particular religion, the abuse of religion for political purposes, and any discrimination against or persecution of persons practicing a particular religion (Article 12). It also expressly disallows associations aimed at threatening religious, social, or communal harmony or at creating discrimination among citizens on the basis of religion or other protected characteristics (Article 38). The congregation at Suhrawardy Uddyan, with its explicit calls for exclusion and discrimination against the Ahmadiyya Muslim community, therefore appears to contravene these constitutional provisions.

Beyond constitutional protections, several forms of expression documented in the dataset may constitute offences under the Penal Code, 1860. Calls for expulsion, declarations branding Ahmadiyyas as kafir, and demands for state discrimination or economic boycotts appear to engage statutory prohibitions on promoting enmity between groups (sections 153A and 505(d)). Meanwhile, the posts also likely amount to injuring religious sentiments (sections 295A and 298), intentional insult (section 504), incitement to commit offences (section 505(c)), criminal intimidation, and threats to person or property (section 503). Additionally, false claims, if any, about private actors such as PRAN-RFL Group could constitute defamation (section 499). As the instances involved coordination and collective planning, the material may also fall within the ambit of criminal conspiracy (sections 120A and 120B).

Finally, the dissemination of calls to declare Ahmadiyyas non-Muslim, to expel them from Bangladesh, or to impose discriminatory state treatment may engage the Cyber Security Ordinance, 2025. Under this law, the publication or promotion of religious or ethnic violence and hate speech in digital spaces is criminalized (section 26). Given the digital nature of much of the content analyzed and the explicit targeting of a religious minority, the material appears capable of meeting the statutory threshold for liability under this provision.

Overall, when assessed against applicable domestic constitutional, criminal, and cyber-security laws, the documented UGC appears to contravene multiple legal protections designed to safeguard religious freedom, equality, and public order in Bangladesh.

Methodology

Data Collection: The dataset for this analysis consists of 93 Bangla-language Facebook posts. These posts were identified using a list of targeted search keywords related to the Ahmadiyya community (including ‘আহমদীয়া’, ‘কাদিয়ানী’), to Khatme Nubuwwat (‘খতমে নবুওয়ত বাংলাদেশ’), and common hateful and pejorative terms used in this context (such as ‘কাফির’ and ‘অমুসলিম’). Content was collected from publicly accessible pages and profiles in the period immediately following the 15 November 2025 Suhrawardy Uddyan rally. While a broader range of terms and phrases circulated in connection with the rally and its messaging, these keywords captured the vocabulary that appeared consistently across the majority of the related posts; in this sense, the selected keywords functioned as common linguistic anchors linking otherwise varied content. It also enabled us to ensure consistency and comparability of findings across a defined set of themes, while avoiding overextension into more diffuse issues that may have undermined analytical coherence.

Language Preference: Bangla is the official language of Bangladesh and the most widely used medium of communication both online and offline, particularly in everyday interactions as well as mass political mobilization in the recent past. While English is also used in Bangladesh, its usage is comparatively limited and largely confined to specific demographic groups. Given the predominance of Bangla as the primary language for disseminating messages to broader audiences, this analysis intentionally excluded English-language search keywords. Moreover, incorporating English terms would have required a substantially expanded scope and timeline of inquiry, beyond the parameters of the present study.

Platform Preference: Facebook was selected as the primary platform for two main reasons. Firstly, it is the most commonly used social media platform in Bangladesh, and in recent years served as a key locus of political messaging and mass mobilization. An initial scan of other popular UGC platforms, such as TikTok and Instagram, revealed comparatively limited UGC related to the rally or its messaging. This appears to reflect both the user demographics of those platforms and their design features, which are less conducive to the sustained dissemination and coordination of mass-mobilization content than Facebook’s interface and network structure. Second, this report is designed as an early diagnostic of a discrete post-event surge, expanding data collection across multiple platforms would have significantly widened the scope and timeline of inquiry. Data collection on Facebook relied on a combination of manual and automated methods, including technical workarounds, unique to the platform, which are not replicable on other UGC platforms; developing different data collection methodologies for each such platform was not feasible within the time constraints.

Thematic Coding: Each post was manually coded into one or more thematic categories derived inductively from the dataset: (1) demands for state declaration of Ahmadiyyas as non-Muslim; (2) explicit labeling as kafir; (3) calls for expulsion or denial of residence in Bangladesh; (4) references to Jamaat-e-Islami’s pledge to declare Ahmadiyya non-Muslim if in power; (5) broader mobilization by political parties; and (6) calls for boycotts of products allegedly associated with Ahmadiyya individuals or businesses. It is important to note that these themes frequently overlap. In addition, because posts were translated from Bangla into English for analysis and reporting, some linguistic nuance and semantic force may not map cleanly onto direct English equivalents. As a result, certain categories may appear more similar, or their distinctions less clear, in English than they are in the original Bangla. Additionally percentages reported for each theme refer to the share of sampled UGC tagged under that theme. Moreover, the percentages are rounded for readability; totals may therefore exceed 100%.

Legal Analysis: The coded themes were then assessed against two normative frameworks. First, Meta’s Hateful Conduct Policy, with a focus on provisions relating to hate speech, calls for exclusion or expulsion, and incitement to discrimination or violence. Second, Bangladesh’s constitutional and statutory framework, including provisions on secularism, equality before the law, non-discrimination, freedom of religion and movement, and relevant offences in the Penal Code, 1860 and the Cyber Security Ordinance, 2025. This analysis is intended as an indicative legal assessment; it does not purport to be exhaustive or to serve as a substitute for judicial interpretation.

Limitations

This study has several important limitations that should inform the interpretation of its findings.

Limited and Purposive Dataset: The dataset is small and purposively constructed. It captures only a narrow slice of the overall information ecosystem: public Facebook posts containing specific keywords in a short time window after the 15 November 2025 rally. It does not include content on other platforms (such as YouTube, TikTok, Telegram, or closed WhatsApp groups), nor does it systematically cover private or closed Facebook spaces. In addition, the analysis does not examine comment threads, reactions or interactions within those threads, nor does it review other platform features such as Stories or Reels. The findings are therefore illustrative rather than statistically representative of all anti-Ahmadiyya discourse in Bangladesh.

Keyword and Format Constraints: Reliance on a fixed set of Bangla keywords means that posts using more coded or euphemistic forms of hate speech may not have been captured.

Language Scope: This analysis is limited by its focus on Bangla-language content. While this choice reflects the dominant language of public communication and political mobilization in Bangladesh, it necessarily excludes English-language posts and other multilingual or mixed-language content, as well as non-textual or indirect forms of expression, such as reactions, emojis, or coded language, that may also circulate online. As a result, certain forms of discourse, particularly those targeting more urban, elite, or internationally oriented audiences, may not be fully captured. The findings should therefore be understood as representative of Bangla-language mobilization dynamics, rather than as an exhaustive account of all linguistic or symbolic forms through which anti-Ahmadiyya narratives may be expressed.

Assessing Meta’s Enforcement Measures: The report infers the apparent absence of “break glass” measures and effective algorithmic moderation from the continued visibility and wide circulation of harmful content, despite advance reporting on the planned rally. However, Meta’s internal decision-making processes, technical thresholds, and enforcement logs are not accessible to the authors. As a result, it is not possible to definitively establish what specific automated or human interventions, if any, were attempted by the platform, or why particular items remained visible. Conclusions regarding moderation lapses are therefore appropriately cautious and are limited to what can be observed from the sampled corpus.

Legal Assessment and Stakeholder Perspectives: The legal analysis is based on the text of relevant constitutional and statutory provisions and on the publicly observable content of the posts. It does not encompass potential defences, prosecutorial discretion, or judicial practice. Likewise, the report does not include interviews with representatives of the Ahmadiyya Muslim community, the government, or Meta, which would be necessary to build a fuller picture of impact and response.