Recent shifts in U.S. government funding priorities have created a severe crisis for global humanitarian and human rights work, slashing financial support for civil society organizations (CSOs) and disrupting essential efforts to protect fundamental freedoms. The impact has been particularly devastating in Global Majority countries, where many organizations are now struggling to sustain their operations. To understand how this crisis has affected the internet freedom and/or digital rights sector specifically within Global Majority countries, we conducted a survey of impacted organizations. This policy brief highlights key findings from the survey, coupled with publicly available data, and identifies the most affected areas of work and those that have remained relatively stable.

Many CSOs in this sector are now scaling back operations, laying off staff, or shutting down entirely. Beyond the immediate financial strain, this crisis has exposed a deeper structural vulnerability: years of dependence on U.S. government funding have created a fragile ecosystem where political shifts can destabilize essential human rights efforts overnight. Decades of tireless activism and hard-won progress now hang in the balance. In many cases, authoritarian governments are seizing on this instability to justify harsher crackdowns on civil society, escalating legal and political threats against human rights defenders, academics, activists and journalists.

Between February 1 and March 28, we conducted a global survey, interviews and a series of closed door discussions with digital rights experts and civil society organizations from the Global Majority. Through these interviews, dialogues and surveys, we tried to better understand the scale of impact, and brainstormed recommendations on necessary next steps. All survey and interview data have been anonymized and aggregated to ensure safety, confidentiality and security of respondents. Questions were optional and respondents had full control of what they chose to share. As a result, only selected and salient aggregated data points are shared in the brief.

This brief outlines strategic suggestions to help the digital rights movement not only withstand the current crisis but also build long-term financial and political resilience. Without urgent action, decades of progress in digital rights and internet freedom could be undone. At the same time, many in the internet freedom community are using this moment to rethink funding structures and lay the foundation for a more sustainable, self-reliant digital rights movement.

Parsing the Data Reveals A Messy Picture of Systemic Disparities

Despite comprising over 60% of the world’s population, Global Majority countries have historically faced significant funding gaps compared to their Global Minority counterparts. An initial analysis of publicly available data on overseas development assistance (ODA) shows of the total $54.9 billion disbursed by U.S. agencies in 2024—for both economic and military objectives—only 36% of aid went to countries categorized as part of the Global Majority, while 64% went to countries and regions in the Global Minority. When adjusted for population, this translated into a per capita aid gap of over $6.00.

However, a closer inspection of the data structure on official U.S. government websites complicates this picture. Aid is not only disbursed to individual countries but also to overlapping regional categories—33 in total—including labels such as “Asia,” “Southern Asia,” “Asia, Middle East and North Africa,” “Eastern Asia,” “Eastasia and Oceania,” “Eurasia,” and “Europe and Eurasia” each treated as distinct regions. On top of that is an ambiguous catch-all category labeled “World.” According to the data dictionary on the government website, the “World” category includes activities reported under both the “Asia Region” and the “Asia, Middle East and North Africa Region,” because “these two regions do not fit within the Department of State regions” used on the site. As a result, these categories often double-count and obscure where funds are actually going, making it challenging to extract clear insights or create meaningful comparisons.

When we exclude regional and “World” allocations and compare only country-specific disbursements, the proportions shift dramatically: a large share of aid does, in fact, go to countries in the Global Majority. This discrepancy raises questions about the reliability of the data for comparative purposes and points to deeper issues in how international aid is tracked and reported.

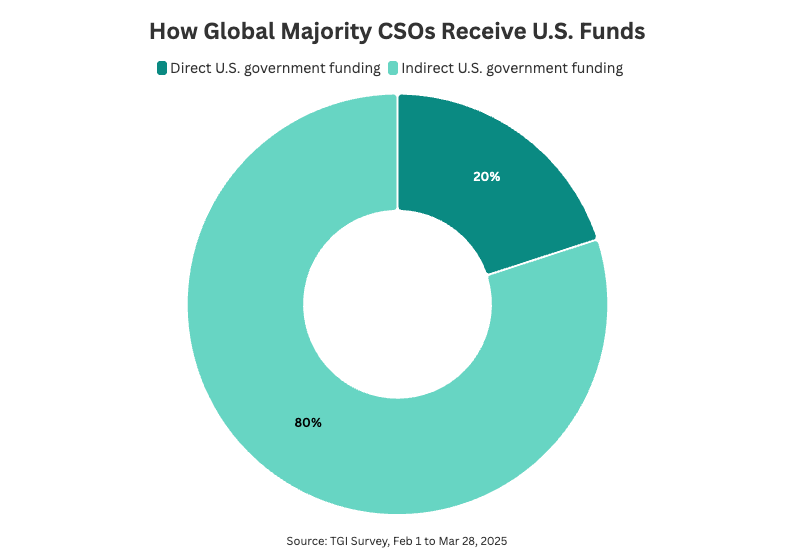

What remains unchanged, however, is the structural inequity in access: organizations in the Global Majority often receive aid indirectly through Global Minority intermediaries. Only 20% of our survey respondents received direct funding from U.S. agencies.

Regional analyses of overseas development assistance (ODA) and financial contributions show similar patterns. For example, U.S. aid to Southeast Asia has consistently been lower than allocations to other regions, according to a 2025 report from Thibi. The report finds that in 2023, cumulative U.S. aid for all of Southeast Asia was less than $1.5 billion, which is far below over $3 billion for Israel and $16 billion for Ukraine. By 2024, aid to Israel and Ukraine surged to over $6 billion and $24 billion respectively, while Southeast Asia could not even cross the $2 billion mark.

This disparity extends beyond general foreign aid distribution and into critical sectors such as internet freedom and/or digital rights. Despite facing greater threats to free expression, digital security, and online privacy, digital rights initiatives in the Global Majority received disproportionately less funding than their Global Minority counterparts. In 2024, only 35% of U.S. funding under the Information and Communication Technology (ICT) category reached the Global Majority, despite its heightened digital safety and rights challenges.

The Scale of Damage

It’s challenging to get exact figures to measure the full scale of impact. Global Majority organizations—especially those working with grassroots digital rights networks—depend on intermediaries based in Global Minority countries to get access to funding. Our survey shows that 80% of those impacted were indirect U.S. beneficiaries.

The impact of U.S. aid restructuring is intensified with budget cuts and reductions in overseas development assistance (ODA) from other countries—such as Sweden, the Netherlands, France, Germany and the United Kingdom—that have historically supported the global internet freedom ecosystem. These cuts can be attributed to a combination of factors, namely reductions in projected GDP growth, and reallocations to defense spending. For example, the Dutch government has announced plans to cut its ODA by €350 million in 2025, with annual reductions expected to reach €2.5 billion by 2027. This decrease is part of a broader strategy to reduce the aid budget from €6.1 billion to €3.8 billion, lowering the percentage of GNI allocated to aid from 0.62% to 0.44% by 2029. Similarly, the United Kingdom has reduced its ODA budget from 0.5% to 0.3% of Gross National Income (GNI), marking the lowest level in 25 years.

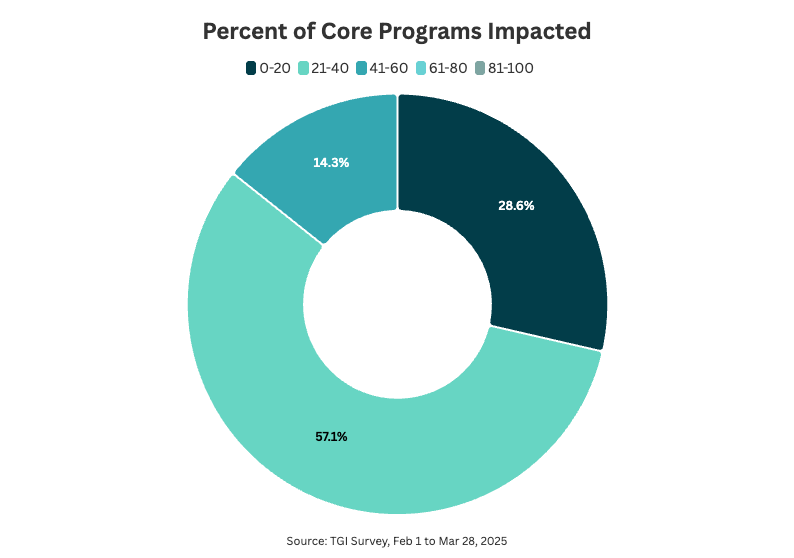

The impact of this funding freeze has been swift and severe. Global survey data from the Tech Global Institute shows that 71% of organizations in the Global Majority have been forced to scale back programs. Of the organizations surveyed, 57% reported that between 21% and 40% of their programs were affected. Just over 14% experienced more severe disruptions, with 41% to 60% of their programs impacted. In contrast, only 28% indicated a relatively lower impact, with less than 20% of their programs affected.

Similarly, a survey by the Collaboration on International ICT Policy for East and Southern Africa (CIPESA) found that 92% of affected organizations in Africa have reduced their programming scope.

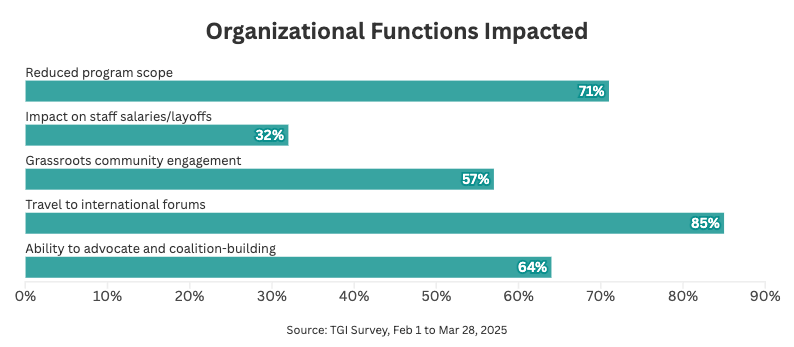

Survey data shows immediate impact on specific functions within organizations that have been most impacted. The most prevalent response has been a reduction in travel activities, which further deepens the longstanding underrepresentation of the Global Majority in internet governance fora and policy-making processes. Over 70% of surveyed organizations reported having to reduce the overall scope of their programs. More than half are no longer able to sustain grassroots community engagement, which not only weakens their presence on the ground but also erodes the credibility and trust with communities that often takes years—sometimes, decades—to build.

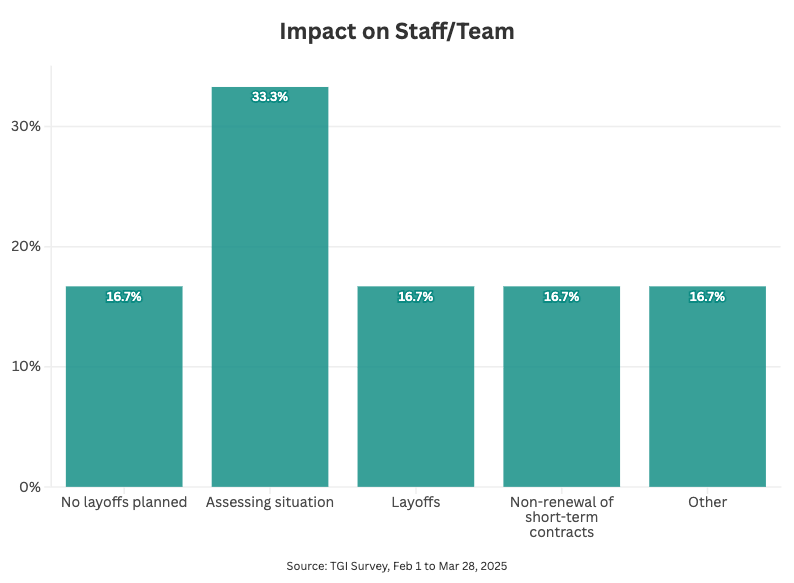

Over 30% of the surveyed organizations reported staffing impacts. Breaking this down further, the third chart shows that among impacted organizations, 33% were actively assessing the situation while already implementing measures such as workforce reductions and non-renewal of contracts. Some organizations, while closely monitoring developments, had not yet initiated layoffs at the time of the survey.

These cuts have had cascading effects: legal aid for persecuted journalists has dwindled, digital safety training for activists has been reduced, and critical network interference monitoring efforts have been abandoned. This crisis has left tens of thousands of pro-democracy advocates, civil society groups, and whistleblowers without essential digital protections at a time when online repression is intensifying. One survey respondent reported that over 5,000 indirect beneficiaries have already been impacted by the funding shortfall.

Structural Barriers to Accessing Funds

Beyond these aid allocation disparities, Global Majority organizations have long struggled with restrictive national foreign remittance laws that obstruct access to foreign aid and investments. Many governments, in part due to anti- money laundering and anti- terrorist financing recommendations proposed by the Financial Action Task Force (FATF), enforce highly restrictive regulatory frameworks to monitor and control financial flows. These often result in complex compliance processes that delay transfers, increase transaction costs, and, in some cases, block funding altogether. In multiple authoritarian regimes in the Global Majority, these national laws are misused to clamp down on human rights defenders and CSOs, exacerbating dependencies on a smaller pool of funds and intermediary organizations. Systemic barriers, both domestic and internationally driven, have placed Global Majority organizations at a structural disadvantage, making them even more vulnerable to financial instability.

With cuts affecting the global ecosystem of civil society and NGO actors, competition for alternative grants has intensified, placing Global Majority organizations at an even greater disadvantage. Instead of competing solely with peer NGOs, they are now up against well-established and large intermediary organizations in the Global Minority.. Established Global Minority rights organizations often have dedicated teams equipped to meet the complex requirements of large international donors and funders, making it much more challenging for smaller organizations, particularly those working on the ground in resource-limited regions and under complex legal regimes, to qualify or secure the funding they need. This dynamic is more adverse for local grassroots digital rights networks who rely on intermediaries or sub-grants to offset compliance burdens and security risks, and whose work is often more directly aligned with the needs and priorities of local communities.

Heightened Security Risks

Beyond financial distress, digital rights organizations are also facing escalating political threats. As funding dwindles and operations shrink, they become more visible as recipients of U.S. aid, which, in authoritarian countries, significantly increases their security risks. These risks have been amplified with recent data disclosures that have increased doxxing and targeting of internet freedom advocates. Governments often seize on these connections to foreign funding as justification for targeting these organizations, labeling them as foreign agents or threats to national sovereignty. As a result, organizations face an increase in politically motivated attacks, such as smear campaigns, legal harassment, and even imprisonment, as highlighted by both our and CIPESA’s findings. These escalating risks exacerbate the already challenging work of digital rights organizations, particularly those on the ground in repressive environments.

“There is a political intent to discredit [organizations] and persecute them.”

The sector is also bleeding talent, with nearly 35% of organizations forced to let staff go. The CIPESA survey adds that some surveyed organizations in Sub-Saharan Africa have lost over 60% of their teams, gutting years of expertise in policy, research, and advocacy.

The immediate [negative] impact on the digital ecosystem [in a Latin American country is] especially critical because the elections are coming up in 2026.

The funding crisis is not just reducing services; it is dismantling critical digital rights infrastructure at a time when online freedoms are under increasing threat. In countries with upcoming elections, the consequences are especially dire. With fewer resources to monitor malicious influence operations, track state-sanctioned surveillance, and support at-risk activists, authoritarian-leaning governments have more room to manipulate digital spaces unchecked.

Over-reliance on private sector support

With reduced ODA, many CSOs will be compelled to turn to alternative sources of funding. The private sector, particularly large tech companies, may become an increasingly important source of financial support. Tech companies have long funded CSO efforts around digital rights and literacy, and entrepreneurship, however, this shift risks creating a funding vacuum that reduces bargaining powers of CSOs, especially those in the Global Majority. Interviewees highlighted tech companies often have their own priorities, which can be driven by profit motives, political considerations, or public relations goals. CSOs may face indirect pressures to align their work with the interests of these companies in exchange for funding. This could impact the independence of civil society, limiting the ability to critique or challenge powerful tech companies or governments, and leading to concerns about “corporate capture” of civil society, on top of existing realities around regulatory and elite capture in under-resourced and/or authoritarian countries in the Global Majority.

Has Anything Survived?

Global Majority organizations that do not rely on foreign funding have been largely unaffected, but they represent only a very small fraction of the broader internet freedom ecosystem. Their financial independence, though, often comes at the cost of limited operational capacity and a reduced ability to scale their impact. While some organizations are beginning to explore alternative funding mechanisms, such as local partnerships, regional philanthropic networks, and private sector support, this shift is gradual and requires significant restructuring.

Recommendations

Without immediate action, decades of progress in digital rights are at risk of being reversed, and the opportunity to transform this crisis into a stepping stone for a more resilient and independent movement could be lost. CSOs respondents to the survey, and those who participated in interviews and focus group discussions suggest the following measures as essential to addressing the current challenges and ensuring the long-term sustainability of digital rights organizations.

-

Prioritize Direct Funding for Local CSOs

International donors must restructure funding mechanisms to ensure that resources directly reach community-based organizations rather than being funneled through large Global Minority intermediaries, where legally possible. Local CSOs are best positioned to address on-the-ground challenges, yet they remain systematically underfunded due to donor risk aversion, complex compliance requirements, and a lack of trust in grassroots financial management. To address this:

- Adopt participatory grant-making models, where local actors co-design criteria and allocate resources based on community needs.

- Simplify reporting requirements for smaller grants to reduce administrative overhead for grassroots organizations.

- Build capacity through multi-year unrestricted funding, allowing groups to allocate resources where most needed rather than tying them to rigid project-based grants.

-

Establish Immediate Emergency Funds

A rapid-response grant program—either by individual funders or pooled funds—must be developed to provide comprehensive support (both financial and non-financial) to organizations at risk of closure. Such systems may include:

- Fast-tracked grants disbursed within 14 days to cover core costs, such as salaries, legal fees, and operational crises, with pre-approved eligibility criteria to accelerate aid during crackdowns.

- Holistic crisis response packages that combine financial aid with integrated non-financial support, including emergency cybersecurity protection, relocation assistance, and legal aid.

- Regional emergency pools managed by trusted local intermediaries to streamline disbursement, supplemented by diaspora networks and pooled donor reserves as alternative channels when traditional funding routes are restricted.

-

Strengthen Coalition Building for Advocacy

Digital rights organizations must unite to push back against repressive policies such as anti-NGO laws and funding restrictions. Joint advocacy campaigns can amplify their impact and force global attention on the shrinking civic space. This requires:

- Formalizing cross-movement alliances, such as linking digital rights with climate justice, labor rights, or feminist organizing, to expand collective political leverage.

- Developing shared tools, including region-specific advocacy protocols and crisis communication protocols, to support coordinated responses.

- Investing in collective legal strategies, such as joint litigation before international human rights tribunals.

-

Diversify Funding Models

Over-reliance on a single funding source is unsustainable. Organizations must explore private sector partnerships, regional donors, and community-driven crowdfunding to ensure long-term financial resilience and reduce vulnerability to geopolitical shifts. This may include:

- Earned-income models, such as offering fee-for-service digital security training, ethical tech consulting or policy advisory services to private sector allies.

- Encouraging larger CSOs to create long-term reserve funds (10% of annual grants), while smaller groups access regional fiscal hosts for financial infrastructure.

-

Strengthen Financial Sustainability

Organizations will greatly benefit from sustained investment in institutional capacity-building to achieve long-term resilience. This necessitates:

- Investment in financial resilience hubs, where CSOs can test hybrid funding models in a supportive environment.

- Promoting fiscal sponsorship programs that allow smaller groups to access global funding without formal registration.

- Developing regional solidarity funds, where CSOs pool resources to mutualize risk (e.g., a revolving loan fund for cash-flow crises).