The Bangladesh Election Commission’s (EC) decision to enable millions of expatriates to vote is overdue and, on paper, encouraging. It operationalises a series of amendments to the Representation of the People Order, 1972 made over the past decade, most recently in November 2025, which together created the legal pathway for non-resident Bangladeshi citizens overseas to cast their ballots through postal voting. Its plan pairs a mobile application, Postal Vote BD, used for voter verification and registration, with paper ballots that are dispatched and returned via traditional postal services.

Digitization of exercising the franchise, however, leans heavily on national identity and electoral infrastructure, including the national identity (NID) and passport databases, maintained by the EC. Yet this infrastructure, and the personally identifiable information that flows through it, operates within an ecosystem systemically vulnerable both to external forms of cyber intrusion and to internal risks of manipulation. As a result, expatriates sharing additional personal details through Postal Vote BD, such as overseas mobile numbers and addresses (that are immediately linked to their existing identity records), are arguably exposed to the same systemic vulnerabilities. One may reasonably contend that the expanded data surface substantially intensifies both the potential for external compromise and the opportunities for internal interference.

Existing data sharing paradigm, practices, and problems

At the centre of the logistical undertaking in organising for the thirteenth parliamentary elections in February 2026 lies the comprehensive collection and accurate management of voter information. With approximately 128 million eligible citizens slated to vote, it is therefore undoubtedly necessary for the EC to collect, process, and retain specific categories of citizens’ personally identifiable information, as a precondition for fulfilling its constitutional and statutory mandates, and to ensure free and fair election. However, the existing data-processing and data-sharing protocols and practices, coupled with several documented incidents of breaches and the absence of an effective data-protection framework, mean that significant vulnerabilities currently exist across the ecosystem, institutional, policy, and technical layers.

As a starting point, Bangladeshi citizens’ national identity system is organized around the NID infrastructure, legally and institutionally maintained by the EC. Data collected includes, but is not limited to, name, birth registration information, gender, nationality, addresses, biometric data (including facial photographs, fingerprints, and iris scans), official signature, profession, medical information, parental and spousal details, and a unique identifying number. Consequently, this infrastructure functions as the core railroad for most identity verification across ministries, statutory bodies, and other public institutions, as well as non-governmental operations such as banks and financial institutions, telecommunication operators, and donor-funded programmes. Over 180 entities reportedly maintain formal arrangements with the EC to directly access citizens’ data in real-time, under sections 14 and 16 of the National Identity Registration Act, 2013. However, underlying this formal layer exists a sprawling secondary ecosystem of informal exchanges, legacy databases, vendor pipelines, and subcontractor chains through which data continue to circulate without meaningful oversight.

First, the opacity surrounding data-sharing arrangements significantly constrains public scrutiny of the safeguards protecting citizens’ personal information. At the system level, it remains unclear whether the infrastructure maintained by the EC, or the systems used by authorized external entities, are protected by adequate technical measures against internal and external intrusions. Likewise, it is equally obscure whether contractual obligations sufficiently bind external entities to maintain rigorous data-protection standards once they obtain access.

Evidence indicates that, in practice, copies of citizens’ data are routinely shared and repurposed, travelling far beyond authorized entities through formal and informal vendor back-ends and subcontractor chains, mostly operating outside clear and enforceable guardrails. For instance, in February 2025, an investigation found that five institutions with authorized access had shared citizens’ data with third parties. Subsequently, in May 2025, two additional institutions were found responsible for mishandling citizens’ data. Of these seven institutions, two were private financial service providers. These incidents are not aberrations but manifestations of a pervasive culture of institutional indifference across the stack, and follows an incident in 2024 involving data exfiltration by an organized cybercrime network. Earlier, in 2023, another breach exposed tens of millions of citizens’ records, apparently due to a misconfiguration in the systems maintained by the National Telecommunication Monitoring Center.

Taken together, these incidents point to a recurring pattern: multiple and overlapping access points, weak data-minimisation and purpose-limitation safeguards, non-standardized contractual arrangements, and limited avenues for redress when things go wrong. Absent transparency around how data-sharing arrangements are structured and operationalized, or even the outcomes of investigations announced after each incident, it is nearly impossible to assess whether unlawful exposures stemmed from institutional, technical, contractual, or individual failures. Suffice to say, however, these successive high-profile breaches raise more questions than answers about the vulnerabilities that exist within the ecosystem and across each of its constituent layers.

Second, compounding the vulnerabilities across the ecosystem is the absence of a robust and enforceable policy framework capable of meaningfully protecting citizens’ personal information. For example, the National Identity Registration Act, 2013 mandates confidentiality and criminalizes unauthorized access and disclosure by both public and private data handlers. Additionally, successive cybersecurity legislations, including the recently enacted Cyber Security Ordinance, 2025, criminalise attacks on critical information infrastructure (such as the NID database), along with other forms of improper access to or misuse of personal information. However, there are conspicuous enforcement gaps, with no visible oversight mechanisms, investigative follow-through, or remedial action, despite multiple high-profile breaches in recent years.

Similarly, the recent enactment of the Personal Data Protection Ordinance, 2025 and the National Data Management Ordinance, 2025 has done little to materially mitigate these vulnerabilities. As observed by Tech Global Institute, for instance, broad exemptions and “necessity” provisions place most government data-processing activities beyond the reach of statutory protections, eroding public accountability where breaches result from inadequate safeguards or systemic mismanagement. Coupled with unclear data localization requirements and opaque data-sharing arrangements, these provisions risk entrenching unchecked state access and enabling continuing surveillance without meaningful oversight. As such, the existing policy frameworks reflect a design and implementation landscape in which obligations are articulated but rarely operationalized, leaving significant gaps between formal protections and the realities of daily data governance. Against this backdrop, any new electoral workflow that leans on NID inherits, not resolves, these weaknesses.

Did Postal Vote BD introduce a fresh layer of exposure?

Postal Vote BD does not necessarily introduce newer risks, rather it risks amplifying pre-existing vulnerabilities. According to the user guide published by the EC, the app requires eligible non-resident Bangladeshi citizens to register by submitting selfies, both passport and NID information, and additional information such as mobile phone numbers, addresses, and geo-location. Each of these steps, therefore, generates new records, logs, and metadata across electoral infrastructure and vendor environments, thereby expanding the overall attack surface.

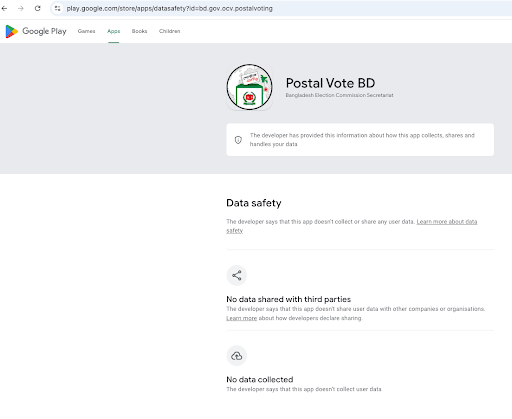

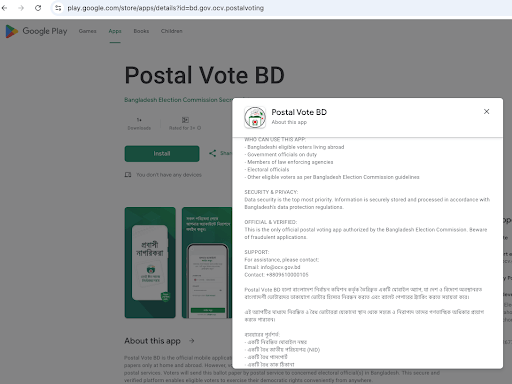

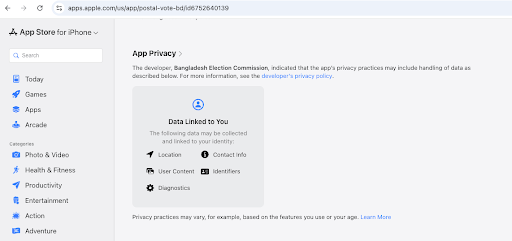

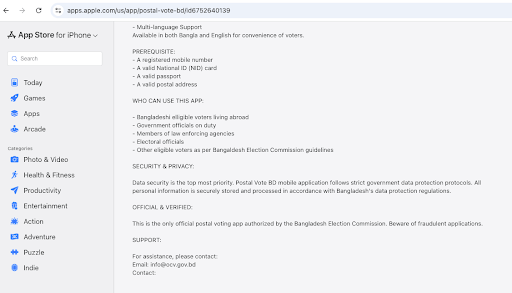

During an attempt to download the app from Google Play Store at 1:00 PM (Dhaka time) on November 19, 2025, the developer indicated that it would not “collect or share any user data” or “share user data with other companies or organisations” (Screenshot 1, see below). Yet, on a closer scrutiny, the app’s official description claims that “[i]nformation is securely stored and processed in accordance with Bangladesh’s data protection regulations” (Screenshot 2). On the Apple App Store, accessed at 1:20 PM (Dhaka time) the same day, the privacy disclosure page states that the app will collect and process user location, contact details, content, identifiers, and diagnostic information (Screenshot 3), with the developer description claims adherence to “strict government data protection protocols” and promises that personal information will be “securely stored and processed in accordance with Bangladesh’s data protection regulations” (Screenshot 4). When the developer’s privacy policy link was accessed, it redirected to a missing-page notice (Screenshot 5), and no official privacy policy was available at the time.

Collectively, the inconsistencies between what is disclosed, what is collected, and what is actually governed underscore the fragility of the app’s security posture. an ecosystem already characterized by opaque data flows and weak enforcement, the introduction of this app risks further normalizing insecure practices and deepening citizens’ exposure to misuse, interception, or unauthorized access. Given, further, the app’s non-public architecture, any independent assessment of its technical robustness is virtually impossible. As such, considering the additional data collected will, in practice, flow through the same loosely governed interfaces and infrastructure maintained by the EC, it is reasonable for ordinary users to be concerned that their information may circulate across systems with both public and private access, under uncertain protections and with few meaningful avenues to contest misuse or seek remedy should breaches or improper handling occur. If recent history is any guide, the additional information collected from expatriates may also be shared or repurposed beyond the scope of its original collection.

Risk mitigation through clear, enforceable data-protective measures

Against this backdrop of structural opacity, weak safeguards, and limited recourse for citizens, extending postal voting to the diaspora can still be achieved without eroding confidence in the process, but only if data governance is treated as core component of electoral infrastructure rather than as an administrative afterthought. In the short term, the risk environment for Postal Vote BD is shaped far more by the existing vulnerabilities in the ecosystem than by the still-nascent data-protection regime, making targeted, immediate safeguards essential.

As a starting point, the EC can establish a publicly accessible set of internal operational rules for its staff and vendors, outlining what data are collected, where they are stored, how breaches or misuse will be handled, strict limits on collection to only what is necessary to confirm identity and send and receive ballots, and defined retention periods. Access should be confined to specific units and named individuals within the EC and its key vendors, with every instance of access logged to enable precise tracing of who viewed which records and when.

Equally crucial is the need to reverse a long-standing pattern in which government apps treat privacy notices as generic, incomplete, or merely symbolic. Postal Vote BD cannot repeat that practice. Its privacy policy must serve as the central public document explaining, clearly and in plain language, how voters’ information is handled and what rights they have. At a minimum, it should list all categories of data collected; explain why each is needed and at which stage; describe where the data are stored, who can see them, and whether they are shared with external entities; and state unequivocally that the information will not be used for unrelated purposes without a lawful basis and prior public notice. Additionally, the policy must be written in non-technical language, easy to find in the app and on relevant websites, and made available in both Bangla and English. If the EC treats this document as a binding public commitment and aligns its internal practices accordingly, the privacy policy can become a practical instrument of governance and audit rather than a formality. In a fragile information ecosystem, such clear, enforceable commitments represent one of the most immediately achievable ways to reduce risk for Postal Vote BD while bolstering public trust in the broader electoral process.

The bottom line

Bangladesh is right to widen the franchise to its diaspora but it is risky to assume that a fragile data ecosystem can safely carry the load without reform. The core issue is not that data are being collected, but whether obligations to minimize, protect, and account for that data are being met in a way that reflects the actual risk environment. The existing weaknesses are known and the new ones are foreseeable. Unless the EC addresses the first and mitigates the second, Postal Vote BD risks becoming another example of how an app designed to expand democratic participation can, inadvertently, make trust in the process harder to sustain.